Not long ago, a lawyer walked into a courtroom with a brief partly written by an AI assistant. The filing confidently cited several past cases that supported his argument. There was only one problem.

None of those cases existed.

The citations were not typos. They were not malicious. They were hallucinations: fluent, authoritative, and completely fabricated. The story traveled through law firms and boardrooms faster than any legal memo.

It captured something executives keep discovering the hard way: modern language models are both astonishingly capable and strangely unreliable. They can draft contracts, summarize earnings calls, and translate dense research, then in the same breath invent sources, dates, or even entire companies.

So the question in conference rooms is simple, and a little exasperated:

Why can this thing sound so smart and still make stuff up?

The answer has less to do with hype, and more to do with how these systems are built in the first place.

The Machine That Predicts Your Next Word

Strip away the marketing gloss, and a large language model is a very ambitious autocomplete.

Provide it with some text, and it will assign a probability to each potential next token: the subsequent word, punctuation mark, or fragment. Then it picks one, appends it, and repeats this process again and again until you have an email, a policy memo, or a poem.

Behind the scenes, the model is trained to approximate a conditional probability:

Given everything I have seen so far, what is the most likely continuation of this text?

There is no special label in the training process that says “this sentence is true” or “this paragraph is false.” Instead, the model adjusts its internal parameters so that its predictions match its training data as closely as possible.

If millions of documents say “Paris is the capital of France” and almost none say “Lyon is the capital of France,” the model learns that the first sentence is a very likely continuation and the second is not. In that way it absorbs patterns that correspond to real facts about the world.

Truth arrives as a side effect of statistics, not as a separate principle.

That works impressively well most of the time. It is also where the trouble begins.

When Statistics Collide With Reality

In real use, three forces conspire to produce hallucinations.

1. Ambiguous input

Ask a model, “Tell me about the recent banking crisis,” and it has to guess what you mean.

Which bank? Which country? Which year? Does “crisis” refer to a run on deposits, a regulatory finding, or a stock price collapse? The model does not see your news feed or your inbox. It only sees your sentence.

From its perspective, there are many plausible worlds compatible with that question. It must pick one and write as if that had been your intent all along. Occasionally it lands on the episode you meant. Occasionally it writes a confident essay about the wrong one.

Humans typically hesitate and ask, “Which crisis?”

Models keep typing.

2. A frozen snapshot in a moving world

Most large models are trained on data that is months or years old. Chief executives change. Products launch, pivot, and shut down. Regulations are proposed, watered down, and quietly shelved.

The model does not sip coffee and read the morning paper. Yet the probability engine is perfectly willing to speak in the present tense about anything you ask. When the world has moved on, the “most likely continuation” inside the model can be flatly wrong.

Think of a brilliant analyst who had perfect knowledge at the end of 2022 and then never read another filing.

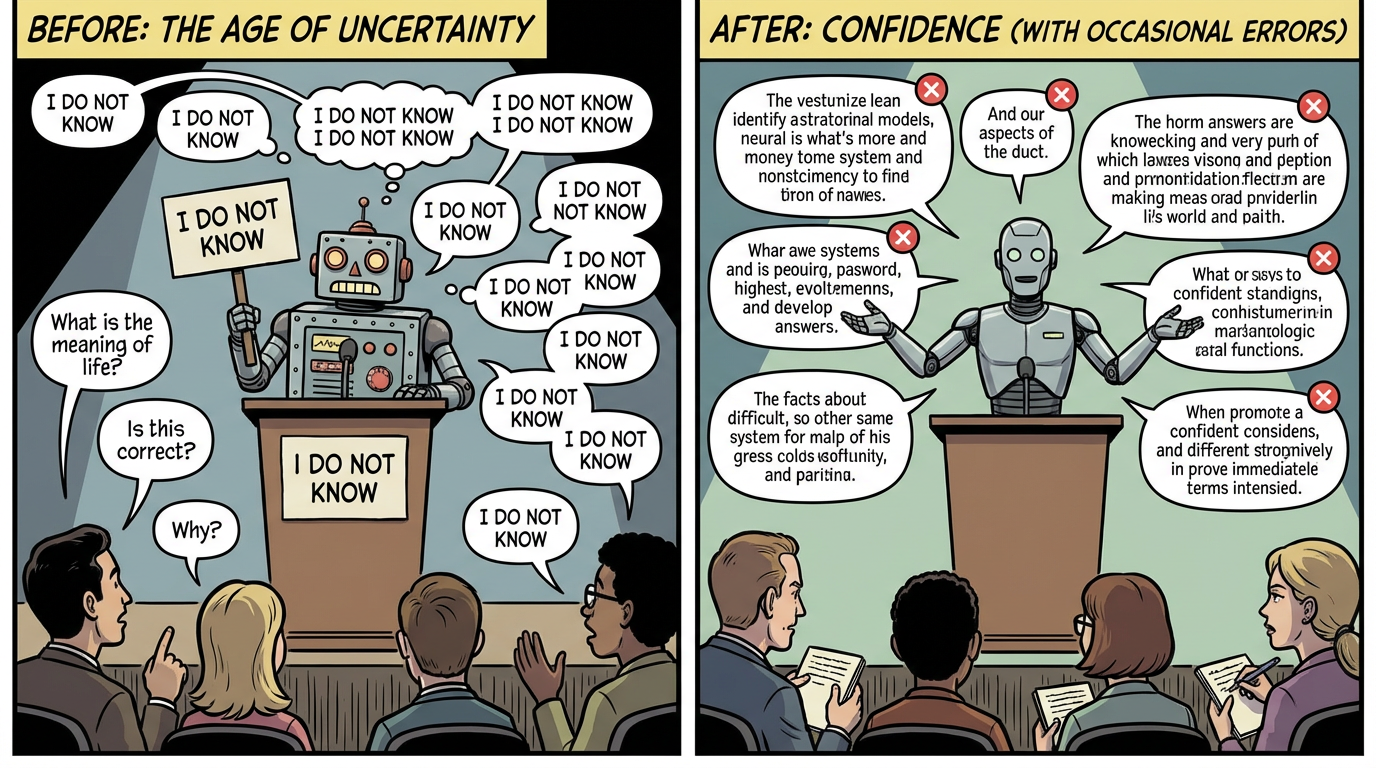

3. The “always answer” expectation

Then there is a product decision that quietly amplifies everything.

Most commercial systems are tuned to be helpful and decisive. They are rewarded for sounding confident, avoiding awkward gaps, and providing complete answers. “I am not sure” is treated as a last resort, not a default.

Put those incentives on top of a statistical engine that must always choose a next token, and hallucinations stop being weird edge cases. They become a predictable byproduct of the system’s objectives: never leave a user empty-handed.

Combine ambiguous questions, a stale snapshot of the world, and a cultural aversion to saying “I do not know,” and you get exactly what we see: occasional, smooth, indefensible nonsense.

Is This Really “Mathematically Inevitable”?

At this point, the conversation often jumps to a dramatic claim: it is “mathematically impossible” for language models not to hallucinate.

That sounds powerful. It is also not quite right.

One can define a model that answers every question with a single phrase:

“I do not know.”

This is still a valid probability distribution over text. It never states a false fact. It never hallucinates. It is simply useless.

Or consider a toy model trained only to answer two questions: “What is 2 + 2?” and “What is 3 + 3?” with perfect training data, and no other inputs allowed. It will always answer “4” and “6.” Zero hallucinations. The mathematics is identical. The scope is tiny.

So conditional probability alone does not force hallucinations. What it does is combine that mathematics with the ambition of the task.

In a more realistic setting, something like this holds:

- The system is expected to answer a wide variety of questions about the real world.

- It has finite, imperfect training data.

- It does not have guaranteed, complete, up-to-the-minute access to external information.

- It is discouraged from declining to answer.

Under those conditions, the probability of sometimes being confidently wrong can be lowered but will always exist.

This is not unique to machines. A human doctor who is never allowed to say “I do not know” will eventually give dangerously confident answers on rare diseases. A financial analyst who must always produce a forecast will miss some turning points.

The difference is throughput. A human’s mistakes are bounded by the number of conversations they can have in a day. A model’s mistakes are limited only by server capacity.

Why Truth Still Shows Up In A “Likelihood Machine”

If these systems are not trained explicitly on truth, why do they often get facts right?

Because the modern information ecosystem, for all its noise, contains a great deal of accurate, structured knowledge. Well-edited books, encyclopedias, financial statements, regulations, scientific articles, and carefully curated websites all show up in the training mix.

Stable facts about the world recur again and again: the capital of France, the formula for compound interest, and the layout of a balance sheet. Matching those patterns is the easiest way for the model to minimize its training loss.

Pure fabrications either show up rarely or are surrounded by markers that they are fiction, parody, or speculation. The model learns that sentences like “Harry Potter won the 1998 World Cup” do not belong in sober discussions of actual football.

In that sense, the model does care about truth, but indirectly. It learns that statements that would not embarrass a careful editor tend to be high-probability text.

The catch is that this connection is statistical. When questions are rare, new, or underspecified, the link between “most likely continuation” and “actually correct” becomes fragile.

That gap is where hallucinations live.

The Quiet Pivot: From Oracles To Colleagues

Serious builders are now learning to treat language models less as digital oracles and more as powerful but fallible colleagues who need tools and supervision.

Three practical shifts are underway.

1. Teaching models to admit ignorance

Newer systems are trained and fine-tuned to estimate their uncertainty and to be rewarded when they say, “I do not know,” or “Here are several possibilities,” instead of filling gaps with confident fiction.

The result is less cinematic and more usable. A model that occasionally asks for clarification or suggests checking a source is closer to a competent analyst than a magic box.

2. Grounding answers in external data

Rather than relying solely on what the model remembers from training, many applications now connect it to live tools:

- Search engines and document stores, so answers are anchored in specific retrieved passages.

- Databases and APIs serve as authoritative sources of numbers, rather than relying solely on memory.

- The model relies on calculators and code interpreters, preventing it from improvising its way through arithmetic.

In this design, the model is a conductor, orchestrating queries and explanations, while external systems handle facts.

3. Adding critics, not just creators

One model that writes and edits itself is a recipe for overconfidence. Many systems now use multiple agents: one to draft, another to review, and sometimes a third to enforce policies.

The second model is tuned to be skeptical, to ask, “What supports this claim?” and to flag anything that lacks evidence. High-risk outputs get routed to humans for final approval.

It is peer review, just at machine speed.

How To Read AI Answers Like An Adult, Not A Fan

For executives, lawyers, bankers, and anyone else who will increasingly rely on these tools, a few habits help.

- Treat AI-generated output as a pre-draft, not a verdict.

- Please request sources for surprising or high-stakes claims.

- Be suspicious of overly specific details in areas where the model is unlikely to have direct evidence, such as personal histories or breaking news.

- Encourage implementations that allow the model to decline instead of punishing “I am not sure.”

Hallucinations are not a glitch that a clever engineer will someday toggle off in a settings menu. They are the byproduct of powerful statistical machinery applied to an unruly world, under business pressure to answer quickly and confidently.

The technology will improve. The guardrails will become smarter. The combination of models, tools, and oversight will reduce the frequency and impact of fabricated answers.

What will not change is this: a large language model is a brilliant guesser, not an all-seeing judge of truth.

Knowing that, and designing around it, will separate the firms that deploy AI safely and profitably from those that find out about hallucinations the hard way, in public, with everyone watching.